Chagas disease, also known as American trypanosomiasis, is a potentially life-threatening disease caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. It is most commonly transmitted by biting insects known as ‘kissing bugs’ that are infected with the parasite. As people typically show no symptoms for many years, most are unaware they have Chagas. Up to a third of people with Chagas will suffer heart damage that becomes evident only many years later and can lead to progressive heart failure or sudden death. Chagas kills more people in Latin America each year than any other parasitic disease, including malaria.

Global View

- Over 7 million people estimated to have Chagas in the world

- Over 100 million people at risk

- 30,000-40,000 new cases per year

- Over 10,000 deaths per year

- Less than 10% of those infected have been diagnosed

- Endemic in 21 countries across Latin America

- Also present in North America, Europe, Japan, and Australia

Current treatments

The two current treatments, benznidazole and nifurtimox, were both discovered half a century ago.

They are effective against the disease if given soon after infection and appear to be effective in the chronic asymptomatic phase of the disease. However, they have significant drawbacks, including:

- long treatment periods (60-90 days)

- serious side effects

- a high drop-out rate of patients due to side effects

- they have not been proven effective in people with severe chronic symptoms

Patient treatment needs

Chagas disease has been targeted by the World Health Organization (WHO) for elimination but fewer than 10% of people with Chagas have been diagnosed and even fewer have been treated. To eliminate the disease, we need a new drug for both chronic stages of the disease that is safe, efficacious, and adapted to the field. Access to treatment and diagnostics also needs to be greatly expanded. We also need to identify better biomarkers, to measure the impact of treatment and predict who is at risk for developing severe symptoms.

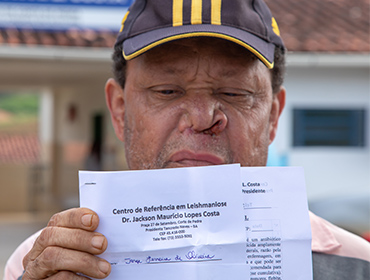

Visceral leishmaniasis, the most severe form of leishmaniasis also known as kala-azar, is a life-threatening disease caused by Leishmania parasites which are transmitted by female sandflies. Visceral leishmaniasis causes fever, weight loss, spleen and liver enlargement, and, if not treated, death. People with both visceral leishmaniasis and HIV are particularly difficult to cure. Visceral leishmaniasis affects the poorest of the poor, being associated with malnutrition, population displacement, poor housing, a weak immune system, and lack of financial resources. The disease is also linked to environmental changes such as deforestation, building of dams, irrigation schemes, and urbanization. A skin condition known as post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) may appear months or years after successful treatment for visceral leishmaniasis. While it is not life-threatening, PKDL can be disfiguring and stigmatizing. People with PKDL can still transmit visceral leishmaniasis, complicating efforts to eliminate the disease.

Global view

- 95% fatal if left untreated

- 50,000-90,000 new cases per year, with only 25-45% cases reported

- 5,710 deaths in 2019

- More than 100x higher risk of developing active visceral leishmaniasis in people living with HIV

- 5-10% of people treated for visceral leishmaniasis develop PKDL

- In 2023, about 83% of cases were reported from 7 countries: Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan.

- About 50% of people infected with visceral leishmaniasis are children

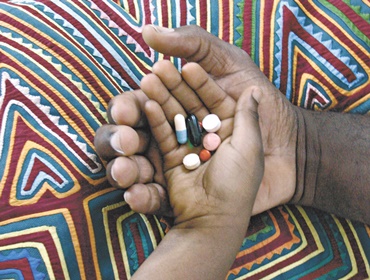

Current treatments

Existing drugs have serious drawbacks in terms of safety, resistance, stability, and cost. They have low tolerability, long treatment duration when used individually, and are difficult to administer:

- Pentavalent antimonials (sodium stibogluconate and meglumine antimoniate)

- 30-day treatment by infusion, if given on its own

- Resistance has been seen in areas where the disease is very common

- Toxic, with risk of serious cardiotoxicity leading to death

- Liposomal amphotericin B

- Much safer and highly effective in some regions: a single 10mg/kg infusion has a cure rate of greater than 90% in Asia

- Expensive and needs to be stored in a fridge

- Miltefosine

- 28-day, twice-a-day oral drug

- Nausea and vomiting are common side effects that may affect adherence to the four-week treatment

- Cannot be used during pregnancy

- Not available in many countries

- Paromomycin

- Three weeks of painful intramuscular injections

- Low-cost formulation

- Associated with toxic effects on the kidneys and ears

- Limited efficacy when used on its own in East Africa

Patient treatment needs

WHO has set the target date for the elimination of this disease in South-East Asia Region by 2026. In order to achieve this goal and improve treatment in other regions, people with visceral leishmaniasis need treatments that are oral, safe, effective, low cost, and short course.

Malaria is caused in humans by five species of single-cell, eukaryotic Plasmodium parasites (mainly Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax) that are transmitted by the bite of Anopheles mosquitoes. In humans, malaria parasites grow and multiply first in the liver cells and then exponentially in the red blood cells. It is the blood stage of the parasite lifecycle that causes the symptoms of malaria in humans. Medicines, in addition to diagnostics, are available to treat and in some cases prevent malaria.

Global view

Malaria remains a serious global health challenge, particularly in the hard-hit African Region.

- An estimated 263 million new malaria cases in 83 countries worldwide in 2023, up from 252 million in 2022.

- This increase was mainly concentrated in five countries (four in Africa and Pakistan) due to factors like catastrophic weather events, population growth and conflict/forced migration.

- Total malaria deaths were stable, with 597,000 malaria deaths in 2023 and 600,000 deaths reported in 2022.

- 76% of global malaria deaths were in children under 5 years old. That's more than 1,200 children dying of malaria every day, mostly in Africa.

- 94% of cases and 95% of deaths were in the WHO African Region.

- Just over half of the deaths occurred in four countries: Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Niger and United Republic of Tanzania.

Current treatments

The control and eradication of malaria demands a multifaceted approach. At present we have a range of good tools, including insecticide spraying and long-lasting, insecticide-treated bed nets help to prevent the transmission of the infection via the mosquito vector. But no preventative strategy is 100% effective – there will always be cases that slip through the net. The current WHO-recommended first-line treatment for the majority of malaria cases is artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). These medicines, in addition to diagnostics, are available to treat and in some cases prevent malaria. Treatment of malaria depends on the malaria species, as well as on the severity of the disease. The World Health Organization's guidelines for the treatment of malaria provides recommendations on topics such as:

- Treatment of uncomplicated p. falciparum malaria

- Treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by p. vivax

- Treatment of severe malaria

- Mass drug administration

- .... and more

Patient treatment needs

MMV’s portfolio focuses on delivering efficacious medicines that are affordable, accessible and appropriate for use in malaria-endemic areas. Specifically, the goal is to develop products that will provide: efficacy against drug-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum, potential for intermittent treatments (infants and pregnancy), safety in small children (less than 6 months old), safety in pregnancy, efficacy against Plasmodium vivax (including radical cure), efficacy against severe malaria and transmission-blocking treatment.